A Brief History of Orcs in Art

An overview of fantasy art by Drew Day Williams

From Hobbiton to Mordor by John Howe

As a miniature sculptor, getting ready to sculpt up some good old-fashioned Orcs for this coming Orctober, I've been asking myself, "What did the original Orcs look like, and where did our image of them come from?"

Compared to much older mythological creatures like Mermaids, Dragons, Cyclopes, or Werewolves, Orcs have only just appeared in popular fantasy. They are so ubiquitous that you'd think that they have been around for as long as the oldest Fairy Tales, but you'd be wrong. In fact Orcs are so recent, I don't even think we'd know what they look like at all if it were not for comic books.

Where to Begin?

Much of what is found in high fantasy illustration today is based on much older art. Even in the Middle Ages, the margins of parchments would have popular drawings of fictitious creatures from dragons to unicorns. When J.R.R. Tolkien penned The Hobbit (1937) and The Lord of the Rings (1956), he drew on many fantastic medieval concepts, and though his use of the name Orc was novel, he based it on the earlier concept of the goblin (1). But it turns out there is no visual history of goblins in art until the mid to late 19th century.

The Golden Age of Fairy Tale Books

After much research in libraries and online, I've come to the conclusion that the popular concept of goblins we've derived from fairy tales wouldn't have come about if it were not for the existence of the printing press, and more importantly, the invention of lithography (by Aloys Senefelder) in 1796. The technology of lithography made it possible to publish detailed illustrations. At first, the art being published was naturalistic, but by the 1860s a trend towards the lavish illustration of fairy tale and folklore novels and compilations took off, and artists were creating detailed images of fantastic places and imaginary creatures as never seen before. And, more importantly to my mind, were becoming a shared visual narrative.

Davy and the Goblin by Charles Carryl

The Princess and the Goblin by George McDonald

By the end of the 19th century, fairy tale illustrators had honed both their skills and their vision, and a collective image of what goblins would look like began to emerge. These forms were largely of diminutive and grotesque dwarfs, or sometimes mischievous flocks of child-like imps. In most cases the goblin was occasionally shown as a trickster, but was otherwise benign. They were also closely associated with the same mysterious otherworld of fairies and elves. The image of the goblin as a rooted, bestial species, as Tolkien described them in The Hobbit, was not a part of that collective image.

The Goblin Market by Arthur Rackham

The dwarfs quarreling over the body of Fafner by Arthur Rackham

Goblins by Arthur Rackham

Goblins by Arthur Rackham

Fantasy is Not Just for Kids!

By the time Tolkien had begun writing The Hobbit after 1930, other science fiction and fantasy authors were creating both short stories and complete novels. But the themes that they were engaging in largely avoided the use of fairy tale tropes, such as elves, dwarfs, or goblins, out of a belief that those were the province of children's literature. Robert E. Howard for example, is now considered the father of the 'Sword and Sorcery' genre in fantasy literature. His Conan series, published in Weird Tales, was complete with fantasy cartography, wizards, sword fighting, and unnatural horrors, but never included any of the signature creature types we now associate with 'High Fantasy' (I'll come back around to how Howard's work influenced our concept of Orcs).

A few of the covers of Weird Tales that featured Howard's Conan stories.

Tolkien, however, developed a deep conviction that elements of fairy tales and folklore could be written for older readers. And so, though The Hobbit was described in its time as a children's book, the nuanced adult themes within it enriched the story such that it was primarily bought for the pleasure of both children and adults.

And this, to put it simply, is the main reason that Orcs exist. After the success of The Hobbit, Tolkien felt encouraged to pursue fantasy writing for adult readers. The Lord of the Rings trilogy, which would later be dubbed the foundation for the 'High Fantasy' genre, was conceived as a departure from standard fairy tales, in a way unlike the more youth-friendly Hobbit. The Lord of the Rings was created over the course of fifteen years as a Romantic Adventure, and as a part of his effort to put distance between his work and the concepts of goblins found in earlier publications I mentioned above, he renamed them as Orcs.

Now it might surprise readers to look back and recognize this, but the appearance goblins in The Hobbit were not described much at all, either in the text or in any art. It was likely that readers at the time would visualize those older fairy tale images of goblins as they read the story, and who could blame them. But in The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien's efforts to redefine his goblins as a more serious adversary, naming them Orcs, and giving them traits more closely akin to those of bitter and monstrous people, conjured entirely different images in the minds of his readers.

And in his readers minds, those images would remain. Because, though the concept of writing fantasy for adults had been proven, fantasy illustration had not. The best fantasy art of that time remained on the covers of pulp magazines such as Weird Tales. The refined craftsmanship of the post Victorian, and Art Nouveau era illustrations were still being dismissed by publishers as only good for children's books, and most of the art used for printings of Tolkien's work, for the first fifteen years or so, was usually severe, stylized, and abstract. In my own quest to research the lineage of Orcs in fantasy art, this period seemed like the Dark Ages. It was a void in fantasy art, waiting to be filled. Fortunately, something awesome was ready to fill it.

What?

What the hell?

Say his name; Frank Frazetta!

But the 'Sword and Sorcery' art of the pulp magazine world continued on, with illustrators developing their craftsmanship and popularity for a growing audience. Comic book art was also improving during this time, and in the mid 1960s, with new developments in paperback publishing, the art of the pulp and comic book scene exploded into the mainstream. And I feel that there is no better example of this transition than the breakout success of Frank Frazetta, and his cover art for the re-publications of Robert E. Howard's Conan the Barbarian series (I told you I'd get back to him.).

Though other contemporaries (such as Boris Vallejo) were also creating spectacular, semi-realistic images of fantasy landscapes and fantasy creatures, I find Frazetta's work to be among the most influential due to his deep background as a graphic artist for the comic book scene, and giving his figures a strong linear quality (Not seen since the Art Nouveau era artists like Arthur Rackham), and also in the way he depicted such carnal and primal scenes that would have never been permitted until those years following the more permissive culture changes of the 1960s. More than any other artist of his time, Frazetta's figures gave hungry fantasy readers their best image of what a throng of fighting Orcs might look like.

Conan the Destroyer by Frank Frazetta

Conan the Conqueror by Frank Frazetta

Frazetta remains my focus here, as I find that it was his works, between 1965 and 1975, that fertilized the ultimate explosion of fantasy media of the late 70s and early 80s. The most recent Ballantine Books publications (1973) had been accompanied by a flood of parallel licenses in Tolkien themed art calendars, graphic novels, and animated film adaptations (This might have been influenced by the death of J.R.R. Tolkien in 1973 and the assumption of Christopher John Reuel Tolkien as controller of the estate). The artistic style of most of these products hewed very closely to that already perfected and popularized by Frazetta. By 1975, even Frazetta himself was being commissioned to create illustrations directly based on Tolkien's work.

Gandalf with Dwarfs by Frank Frazetta

The Witch King and Eowyn

Eowyn Slays the Nazgul by Frank Frazetta

Gollum by Frank Frazetta

And so this is where I found I could sincerely begin to outline our modern depiction of Orcs. Though Frazetta and his contemporaries had access to and sometimes referenced, the gentle, often sweeping, illustrations from those classic fairy tale publications, they infused their versions of fantasy art with the darker themes of sex and violence that grew out of the pulp fiction and comic book industry, as well as the wider generational social changes of their time.

But the figures that Frazetta used to describe Orcs were not like the twisted grotesque little men that populated the illustrations of the Fairy Tales. Developed out of the 'Sword & Sorcery' genre, his Orcs appeared like full sized men, albeit bestial, and ape-like. In Tolkien's writings, his Orcs are seldom described as anything other than rough, unsympathetic people. There is little language to indicate actual bestial appearances, only bestial behaviors. But in Frazetta those animalistic qualities are made graphic and visceral. Canine teeth become prominent, jaws are shown large and jutting, armor is worn piecemeal, if at all, and postures are less like fighting men, and more like enraged beasts.

Orc Army by Frank Frazetta

So Why Are Orcs Green?

As these above evolutions were happening in the graphic arts world of the 1970s, other consumers of Tolkien's literature were being inspired to create another type of art, in the form of games.

Dungeons & Dragons is credited for being one of the first unauthorized adoptions of Tolkien's material in fantasy games. In it, authors Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson, and others, collaborated and codified a list of fantasy creatures as adversaries for tabletop gaming and role-playing. Just as the sub genre of pulp fantasy had broken into the mainstream a decade earlier, so too fantasy gaming was moving from basements and dorm rooms, and onto those same bookstore shelves.

Fueled by the craze for fantasy themed material, their products became popular, and their business, Tactical Studies Rules (TSR) rapidly grew. It's important to notice however, that their first publication was in 1974, and their own descriptions of Orcs and Goblins (listed as two different creature types) took the vague descriptions of Orcs, found in The Lord of the Rings, into a different direction. While Frazetta's contemporaries, fueled by Swords & Sorcery, were expressing Orc's as animalistic men, the Orc's of Dungeon's and Dragons were presented as a half-man, half-beast species. This approach came with signature details such as snouts, tusks, and, oh yes.. green skin.

Hordes of Dragonspear by Doug Chaffee for TSR

Many people wonder about this choice to depict Orc skin as green, as opposed to the "sallow" yellows and browns, or darker colors attributed to them by Tolkien in his works. Some have suggested that this was an effort to establish a distinction for reasons of intellectual property. Other's have proposed that it was a modern sensibility to rebuke the inherent bigotry of Tolkien's Orcs as being described as "mongol types". A few have even suggested that it was the influence of the character of the Green Goblin in Spider Man comics. But I have my own theory as to why TSR established green as the color of Orc skin.

My Own Theory of Why Orcs are Green

The origins of Dungeons & Dragons is found in tabletop gaming. Historical wargaming to be precise. For those who did not already know this, it's in the name of the company, T.S.R.. Tactical Studies Rules. For more detailed (and first-hand) information on this aspect of tabletop gaming history, contact the good people at The Castle and Crusade Society. Because it was with the people from that gaming club (in the early 1970s) that the first fantasy based war gaming was played. Though the historical battle games were played in a variety of ways, they most popular among the creators of Dungeons & Dragons was the use of a sand table and painted Elastolin figures.

At some point, inspired by the general enthusiasm for fantasy, and the heightening popularity of Tolkien in the early 70s, those players began to re-designate, and often re-paint, various historical figures as fantasy creatures other than human. Different scale figures were introduced to represent Ogres or Giants, and figures of soldiers from various cultures or periods would have their faces colored unnaturally to denote that they no longer represented. This was done for the simple reason that there were no tabletop miniatures for fantasy battles before that time.

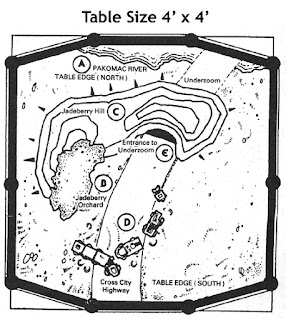

I've enjoyed playing these games myself, with those repainted figures, on that sand table. Well, maybe not the same sand table; I'm pretty sure they're using a rebuilt one. But The Castle and Crusade Society does continue to run those same fun games, these decades later. Here are a few of my images from a battle that I participated in during Garycon. Note the Turkish figures repainted to represent Hobgoblins, the larger 45mm "Natives" painted yellow to represent Ogres, and the much larger scaled Viking painted blue to represent a Frost Giant. (Incidentally, that Frost Giant made mincemeat of the enemy cavalry!)

I won't pretend to know what was happening back at the beginnings of TSR, but it is my theory that the creators of Dungeons & Dragons, when describing their Orcs as green, were probably just carrying over an aspect of their personal experience from their early use of re-purposed historical figures. Perhaps it was a quick and easy means of distinguishing opposing forces among the toy soldiers on a table.

I believe that this choice was made nonchalantly, with no real anticipation that the game would grow in popularity, or that those choices would be copied by other artists and game creators in the following years. Soon after Dungeons & Dragons was first published, other illustrators, such as Tim Kirk, also depicted Orcs with green skin. And in the early 1980s as TSR's sales and marketing accumulated momentum, other game companies began publishing simmilar fantasy rules systems, or developing their own supplemental products, all with the same signature green Orcs.

Road to Minas Tirith by Tim Kirk

Box Art for licensed AD&D Orc miniatures by Grenadier

It Was Not Just Dungeons & Dragons!

Many other game companies entered the market after TSR. Some have persevered to this day, while many others failed. Warehousing and distribution businesses created whole new sections for tabletop games and role-playing products. And in just a few years, specialty gaming warehouses were stocking thousands of products from hundreds of similar companies in an increasingly competitive field. Though many different settings were created, the High Fantasy setting variety, which usually included Orcs, was the most prevalent.

Among these, was Iron Crown Enterprises, who, in the mid 80s, acquired a license to publish a series of role-playing game products specifically based upon Tolkien's Middle Earth. Titled Middle Earth Role Playing (MERP), It was well written and well recieved, and many people still play it to this day. But what is of the greatest interest to me about this, is that they commissioned the renoun historical reconstruction artist, Angus McBride, as their lead cover art illustrator.

Though McBride was certainly inspired by the work of Frazetta and others, he stated that he intended to also hold true to Tolkien's written text. What followed, I feel, was a tour de force of Middle Earth themed illustration, which perhaps exhibits the best fidelity to the subject matter. Painted in the late 80s, his depictions of Orcs still displayed the bestial traits that were popularized by artists in the decade prior, but expressed them with a convincing verisimilitude unique in fantasy illustration.

Denziens of the Dark Wood by Angus McBride

Riders of Rohan by Angus McBride

Gates of Mordor by Angus McBride

Around 1978, a new game company in England pursued an exclusive UK distribution contract with TSR. Games Workshop began as a seller of gaming products with Dungeons & Dragons as their flagship product, but they quickly expanded to carry many other products as well, eventually developing supplemental material of their own.

When their own fantasy wargaming rules, Warhammer, were first published, they happily adopted the same green skin of the ubiquitous Orc. As their business grew, they crafted a signature style to their Orc products, further exaggerating tusks, jutting jaws, and crude animalistic features. This was partly driven by the growth of the tabletop gaming industry, and a developing need to assert intellectual property controls.

Waaargh; Orks, cover art by Wayne England

A decade later, Games Workshop had long since ceased their distribution contracts for TSR and other companies, focusing instead on their own brand, and became a publicly traded corporation (Something largely unique in the tabletop gaming industry).

It's size and global reach attracted the attention of other businesses, eager to develop licenses products in other markets, including the rapidly growing video games industry. One such business was Blizzard Entertainment, who invested development into a Warhammer RTS video game pitch-proposal. That license never materialized, but the studio chose to re-purpose the product they had developed and market it under their own brand. That was how Warcraft: Orcs & Humans was first created, spawning the long series of World of Warcraft products since, and that's the simple reason why their Orcs appear so similar to those of Games Workshop. Ape-like, with tusks, and green skin.

Orc Wolf Rider from Blizzard Entertainment

However, Blizzard's refinement of the Orcs in their games make a notable change to their popular depiction in modern media. Not only for their games products, but for other licensed productions such as the 2016 film, Warcraft. While Tolkien's Orcs were described as a people with no redeming virtues, and other game companies since the 1970s have largely maintained that trope, the World of Warcraft Orcs have been rewritten to include a detailed and sympathetic perspective.

Though still defined as a "warlike race" (2), and fraught with other problematic stereotypes, they are no longer being relegated a simply fodder for heroes to kill. I beleive these changes were made, in part, to avoid any conflict with Games Workshop's intellectual property. Even so, they have moved the general perception of Orcs into a new era. (3)

Durotan and Draka from Warcraft (2016)

That's All I Got? How About You?

And that is what I know about why Orcs look the way they do. I think it is fascinating how rapidly the idea of the Orc captured the imagination of so many people all at once. There are many novels, illustrations, films, and game products, that came and went along that long course of time. Some defied the trends that I've tried to outline.

Also, I'm just a professional miniature sculptor and part-time art teacher. I've got a little GFA and an MFA, not an MHist or PhD. So it is very likely I've overlooked something important, or got a date wrong. I will hope some people who read this, and know some other pertinent stuff, will write back in the comments. I'll gladly insert attributed changes where warranted.

(1) "What was the relationship between Orcs and Goblins?" is a succinct piece from The Tolkien FAQ by William D.B. Loos, and offers the clearest explanation that I have found. http://tolkien.cro.net/orcs/goblins.html

(2) For that I would like to direct you to James Mendez Hodes' recent blog, "Orcs, Britons, And The Martial Race Myth, Part I: A Species Built For Racial Terror" He says just about everything I might say on the topic, but better. https://jamesmendezhodes.com/blog/2019/1/13/orcs-britons-and-the-martial-race-myth-part-i-a-species-built-for-racial-terror

(3) This old piece by G Willow Wilson, "The Orc Renaissance: Race, Tolerance and Post-9/11 Western Fantasy" offers some helpful perspective on the pros and cons of Blizzard Entertainment's modern take on fantasy races and their cultures. https://www.tor.com/2013/07/09/the-orc-renaissance-race-tolerance-and-post-911-western-fantasy

Copyright Disclaimer: Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act 1976, allowance is made for "fair use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing. Non-profit, educational or personal use tips the balance in favor of fair use.